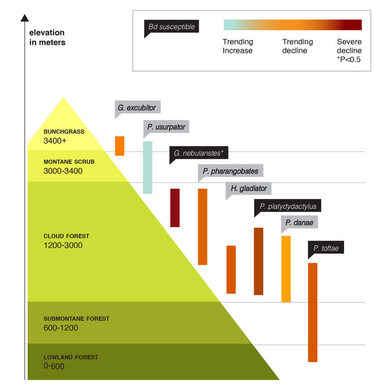

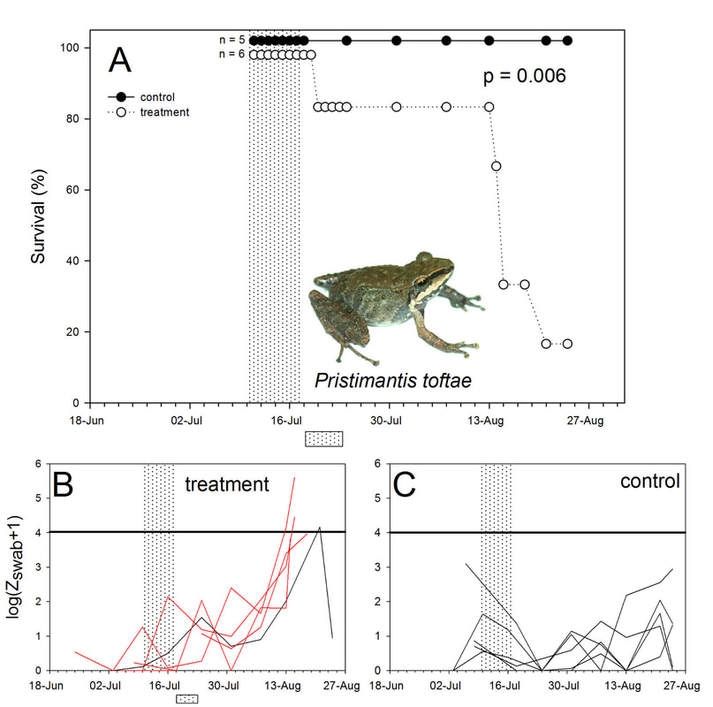

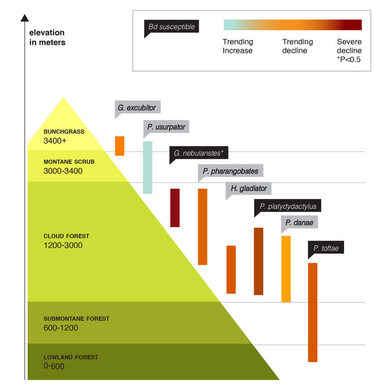

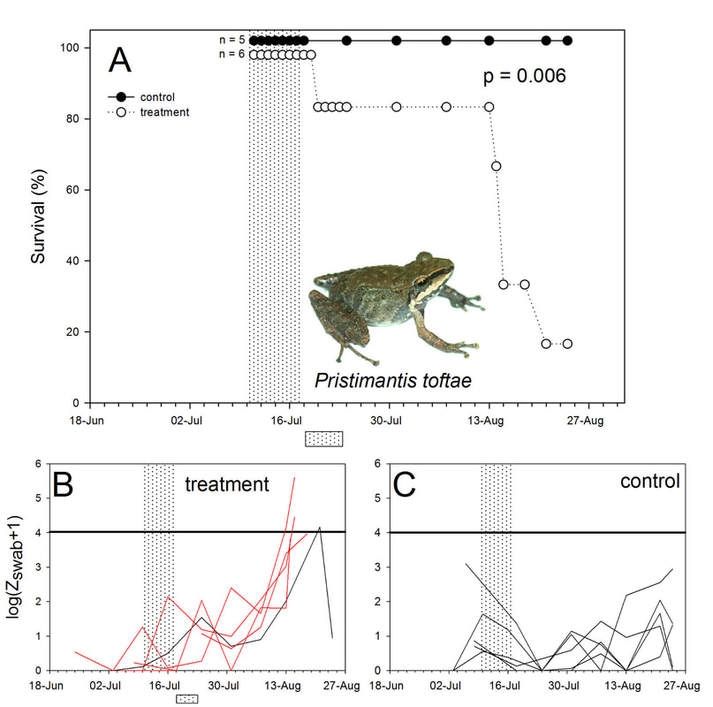

A lab contribution published today explores fungal disease-frog host dynamics in the species-rich frog communities of the eastern slopes of the tropical Andes, near Manu National Park in Peru. We have been studying these communities since 1996, when chytrid disease had not yet caused sharp declines in frog species richness and abundance. Following the epizootic of chytridiomycosis that swept southern Peru in the early 2000s, 19 out of 55 species vanished from the cloud forest (1200-3600 m), as reported previously. Unfortunately most of these species have not been seen since then. But how are the surviving species faring in this environment where chytrid is now established?  Our general approach was to compare species vulnerability to infection by chytrid with observed changes in population abundances for eight common species of frogs. We selected these species to maximize sample size, to provide opportunities for within genus comparisons, and to cover the elevational range where we recorded declines. Our infection experiments were difficult to conduct at the remote Wayqecha Biological Station, but dedication and creativity go a long way towards making things possible. In addition to Vance Vredenburg and Andrea Swei from SFSU, our team was composed by then undergraduate students Emily Foreyt (Gonzaga) and Lauren Wyman (Princeton; shown above), and Jacob Finkle (UC Berkeley), who all co-author our publication.  As shown in the survival curve above and the video below, some "survivors" continue to be susceptible to infection by chytrid. In the example here, Pristimantis toftae quickly succumbs to chytridiomycosis following experimental infection; the videos shows tetanic spasms in a highly infected individual. As pane C shows, most individuals in our "control" group (which was supposed to be negative for disease) were infected at low levels, because our itraconazole baths failed to completely clear infection. Although this limits interpretation of our results, it also suggests that the immunoprotective effect of previous Bd exposure might not be a common response across all amphibian species - in fact we saw little evidence for such effect in our species. Overall, three out of eight tested species are susceptible to chytridiomycosis. Populations of these three species, and of all other species but one, have somewhat to sharply declined during the decade from 1999 to 2009. Phylogenetic relatedness did not appear to be a good predictor of susceptibility: while two Pristimantis species were susceptible, two other species were not. Among Gastrotheca, one was highly susceptible while the second was not; our previous work suggests that anti-fungal skin bacteria might protect the non-susceptible Gastrotheca excubitor.  Does this mean that more species will vanish? While the results of our experiments suggest trouble for several species, other factors such as transmission risks and environmental exposure to fungal propagules play important roles in driving disease-host dynamics. For example terrestrial-breeding frogs such as Pristimantis are less exposed to infection by the aquatic zoospores of the chytrid fungus, because they generally avoid water bodies. On a positive note, populations of some "surviving" species have recently recovered - hopefully a trend that will continue in the future.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

CATENAZZI LABNews from the lab Categories |