|

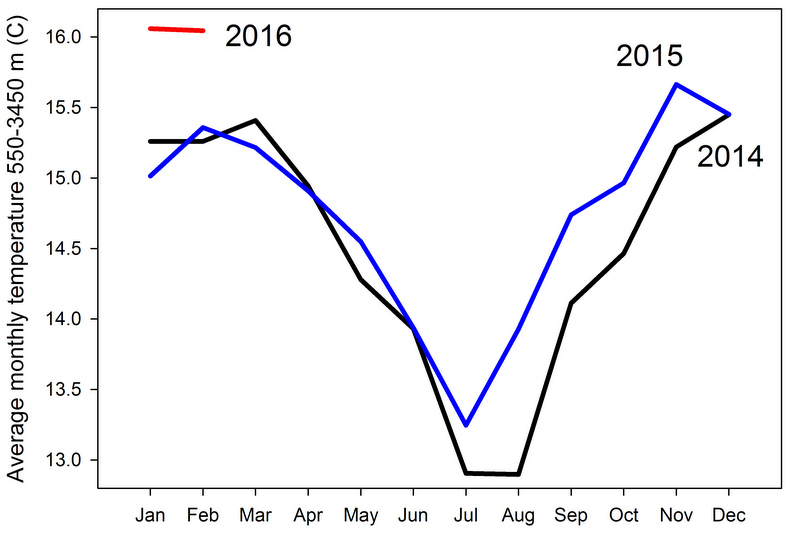

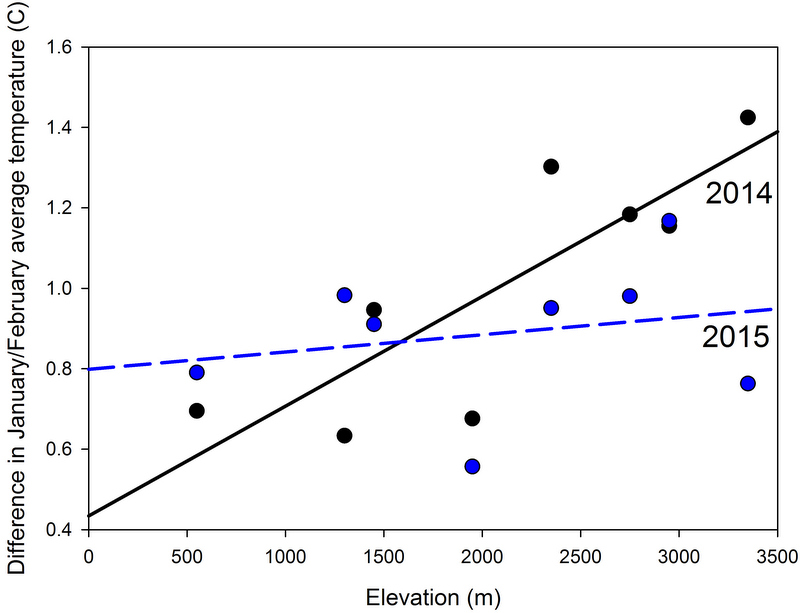

Last year was the warmest year on record but our data from Manu National Park in the eastern slopes of the Peruvian Andes show that January and February 2016 might shatter previous records in the region (January-March are typically the warmest months in this region). We only started tracking leaf litter temperatures (where our study critters the amphibians live) in January of 2014, and thus only have data since that time, but this is probably compensated by the fact that 2014 and 2015 are among the warmest years since records began. Our data for the first two months of 2016 along the elevational transect in Manu from 550 to 3450 m show that January and February 2016 are nearly a degree Celsius warmer than the same months in 2014, and ~0.8 Celsius warmer than the same months in 2015 (see graph below). What is remarkable in these data is that the sensors do not record air temperatures, but temperatures amphibians are likely to experience in their thermally buffered microhabitats, under layers of mosses (at high elevations) and leaf litter (at mid and low elevations). These data suggest that amphibians are unlikely to easily escape warming, even under layers of mosses and leaf litter. The photo shows sensors embedded in agar models being buried under the leaf litter in the montane forest at 900 m, which is the wettest among our monitoring sites. The sensors placed under the deepest layers of mosses (and thus, possibly more buffered against changes in air temperatures) recorded larger increases in warming than sensors placed under the thinner leaf litter. This is possibly caused by higher degree of warming at high elevations, as shown by the graph below which illustrates that average temperatures in the high-elevation cloud forests (above 2000 m) this year exceed by up to 1.4C the January-February averages of 2014.

0 Comments

Alex just got back from spending 2 weeks in Costa Rica with the Forman School Rainforest Project. This project, now in its 24th year, teams up high school students from Litchfield, Connecticut with researchers to conduct studies in the rainforest. This year students conducted projects examining the strength of spider silk, banded neotropical migrant birds, tracked mammals throughout the preserve, recorded animal sounds for Cornell's Macaulay Library, and conducted surveys of the herpetofauna in the buffer zone of Braulio Carrillo National Park. This research was all conducted within the neighboring reserves of Selvatica and Rara Avis. These sites are home to an incredible diversity of plants and animals, and neighbor one of the largest and most unexplored national parks in Costa Rica. The 2016 Spider Team extracting silk from a Nephila clavipes. The silk of these spiders is one of the strongest natural fibers. These students, and the teams before them, have been investigating the sustainable extraction and use of this silk. The 2016 Bird Team mist netted birds throughout the reserve. This year they banded a number of migrants, and recaptured one that was first banded more than 5 years ago. This year's mammal team placed radio collars on a bat and 2 possums this year and tracked their movements. They also mist netted bats to begin assembling a species list for the area, deployed camera traps (capturing a puma and a margay!), and began mapping tapir and peccary movements along the trails. The Bioacoustics Team records bird, frog, and insect songs for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. These recordings can be used in the future for remote biodiversity assessments using auto-identification software (think Shazam for nature!). And last, but certainly not least, the 2016 Reptiles and Amphibians Team! This years team worked alongside Alex and Dr. Twan Leenders (Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History) to survey the herpetofauna of the reserve and collect data on the prevalence of chytrid. They swabbed over 200 frogs, salamanders, and tadpoles in less than 2 weeks.

Here are hopeful herpetologist armed with digging tools before heading to a site where caecilians (likely Oscaecilia) had previously been found. From left to right: Alessandro Catenazzi, Kerry Kriger (savethefrogs.com), Vanessa Luna (Science Coordinator at Villa Carmen), Alex Ttito and Consuelo de las Nieves.  A lab contribution and collaboration with Alex Ttito published today in PeerJ adds one species to the genus Psychrophrynella, a group of highly endemic, high-Andean leaf litter and moss frogs. The name of the new species, chirihampatu, comes from the Quechua words hampatu = toad, and chiri = cold, in reference to the cold environments inhabited by this frog in the upper cloud forest of the eastern slopes of the Andes. This name is also a wordplay with the genus name, which has the same meaning but is composed of Greek words.  The new species was found during a quick biological survey (see our post from last year) in the Private Conservation Area Ukumari Llaqta, in the Japumayo Valley of southern Peru. Ukumari Llaqta, which means "place of the bears", is a legally recognized protected area owned by the Community of Japu Qeros. This beautiful valley is likely to hold additional treasures and new species, including other species of terrestrial-breeding frogs.

This video shows the habitat of the marsupial frog Gastrotheca excubitor and the direct-developing Psychrophrynella usurpator in the highlands near Manu National Park. The misty and drizzly afternoon boosted the calling activity of both species, and a couple of males of the marsupial frogs can be heard in this video.

Articulo publicado por el periódico Correo el 6 de marzo 2016 sobre nuevas especies de fauna descubierta en Perú durante el 2015, incluyendo a la rana dorada de Huancavelica (Telmatobius ventriflavum).

|

Archives

June 2024

CATENAZZI LABNews from the lab Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed