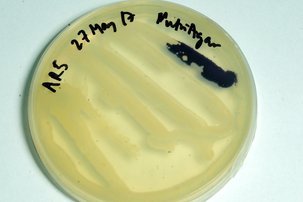

During the last week of May we embarked on a field trip to Reserva Nacional Pampas Galeras, where Andrew is conducting field work for his master thesis. This Reserve was set up, among other reasons, to protect the habitat of vicuñas and to promote their sustainable use. These camelids, which along with guanacos are not domesticated (in contrast with the domesticated llamas and alpacas), produce the finest wool, which is highly prized for luxury clothing.  But the reserve also protects native Telmatobius frogs, which live and breed in streams and torrents, for example the stream in the picture below where young vicuñas are taking a bath, and where Andrew (right, handling an adult frog) is currently doing field work. These populations, like other populations of Telmatobius throughout the Andes have been affected by epizootics of chytridiomycosis. Whereas other species of Telmatobius have been very negatively impacted by this fungal disease, such as the three species previously distributed in Ecuador and most species living in the cloud forests of the eastern slopes of the Andes, the Telmatobius at Pampas Galeras seem to be able to cope with chytridiomycosis. Our collaborator Victor Vargas, in the photo below swabbing an adult female, started monitoring these populations a couple of years ago, and introduced us to the unique ecosystem.  Our collaborator Dr. Sarah Kupferberg, seen in the picture recording the call of the (very rare) males of Telmatobius, joined the team for a week of diatom sampling, tadpole hunting, and other stream ecological studies in the context of Andrew's thesis. Andrew is investigating the ecological consequences of reduced grazing abilities by the very large Telmatobius tadpoles (some weighing up to 25 g). Although chytridiomycosis does not seem to be lethal to tadpoles, it does damage their mouthparts, affecting their diet.  The high-Andean streams where these tadpoles live are dominated by in situ primary producers, mostly epilithic diatoms, which also represent an important source of food for tadpoles. Damage to keratinized mouthparts, as seen in the picture here (upper beak should be entirely black; depigmentation indicates damage), is likely to reduce the tadpole's ability to displace these diatoms from their rocky substrates. In order to study these effects, Andrew is rearing tadpoles in flow-through enclosures. Because of their dominance (along with mayflies) as diatom grazers, disease could then be having important consequences on the functioning of these stream ecosystems by affecting the diet of tadpoles.  As for the question of why adults seemed to have survived epizootics of chytridiomycosis, we won't have an answer for a while, but preliminary surveys indicate that many adults may be protected by one symbiotic bacterium, Janthinobacterium lividum, known to inhibit growth of the fungal disease in co-culture assays, and to protect inoculated amphibians from chytridiomycosis. We isolated this bacterium from most adults, which is unusual for tropical amphibians where this microbe has rarely been recorded. Hopefully these frogs will continue to maintain stable or growing populations in spite of the presence of fungal disease.

0 Comments

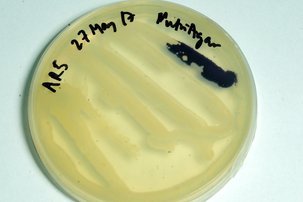

A new paper from the Catenazzi lab (Burkart et al. 2017) suggests that bacteria, but not peptides, play an important role in protecting a Peruvian marsupial frog from chytridiomycosis. Controlled susceptibility trials determined that Gastrotheca excubitor is resistant to chytridiomycosis but its congeneric, G. nebulanastes, is susceptible. It was hypothesized that this finding could be explained by interspecific differences in cutaneous defenses since infection by the disease-causing fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) is initiated on the skin. Two of these defenses, antimicrobial peptides and symbiotic bacteria, have previously been shown to play roles in providing other frogs with disease resistance. We collected peptides and bacteria from both species. Growth inhibition assays using whole peptide mixtures and bacterial isolates were conducted to determine if either defense was anti-Bd in vitro. Although neither species’ peptide mixtures differed in anti-Bd ability, 6/15 G. excubitor bacterial isolates inhibited Bd compared to 1/11 from G. nebulanastes. Furthermore, the G. nebulanastes isolate was the weakest of all anti-Bd bacteria. The frogs shared no bacterial species, and a microhabitat analysis suggested that environment may be an important inoculum since G. excubitor is terrestrial and G. nebulanastes is arboreal.  Understanding what contributes to host resistance is important for informing disease mitigation strategies. The application of anti-Bd bacteria to susceptible frogs has been proposed as a method to prevent chytridiomycosis, and our research corroborates the important role bacteria play in providing this protection. Furthermore, the reproductive strategy of these marsupial frogs likely allows for vertical transfer of bacteria from mother to offspring so that probiotics can proliferate through a population. The implications of our research extend beyond the amphibian-Bd disease system, as beneficial bacteria are likely important host defenses for other diseases. |

Archives

June 2024

CATENAZZI LABNews from the lab Categories |