|

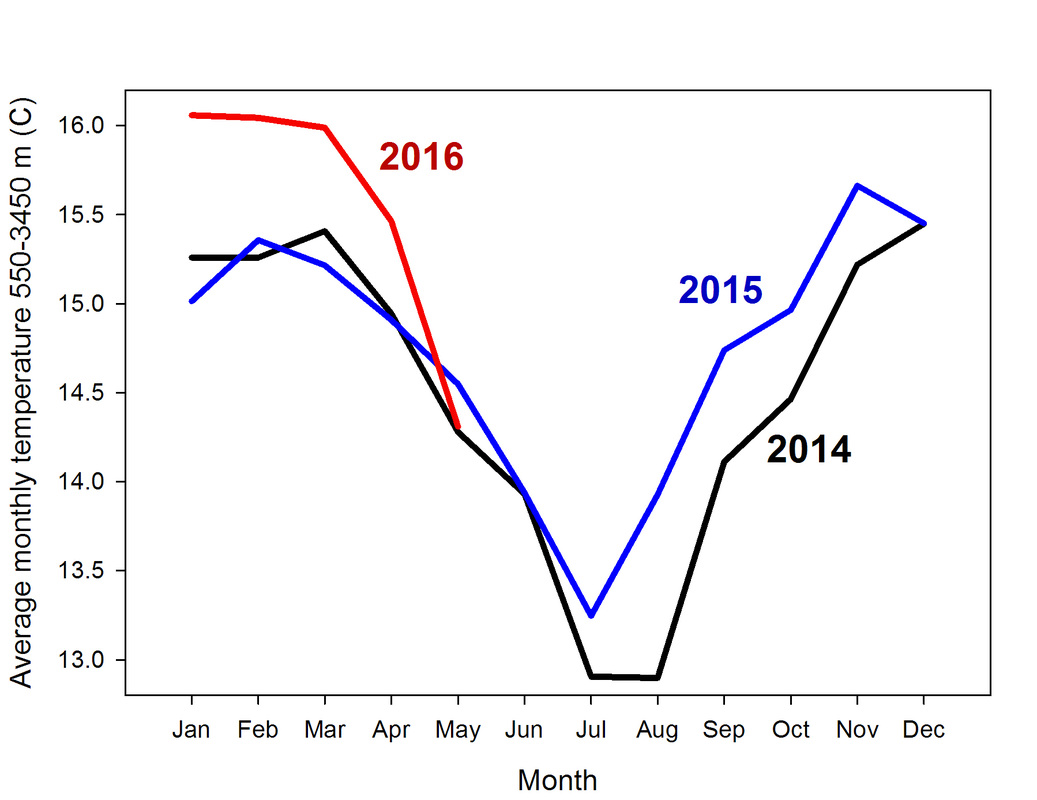

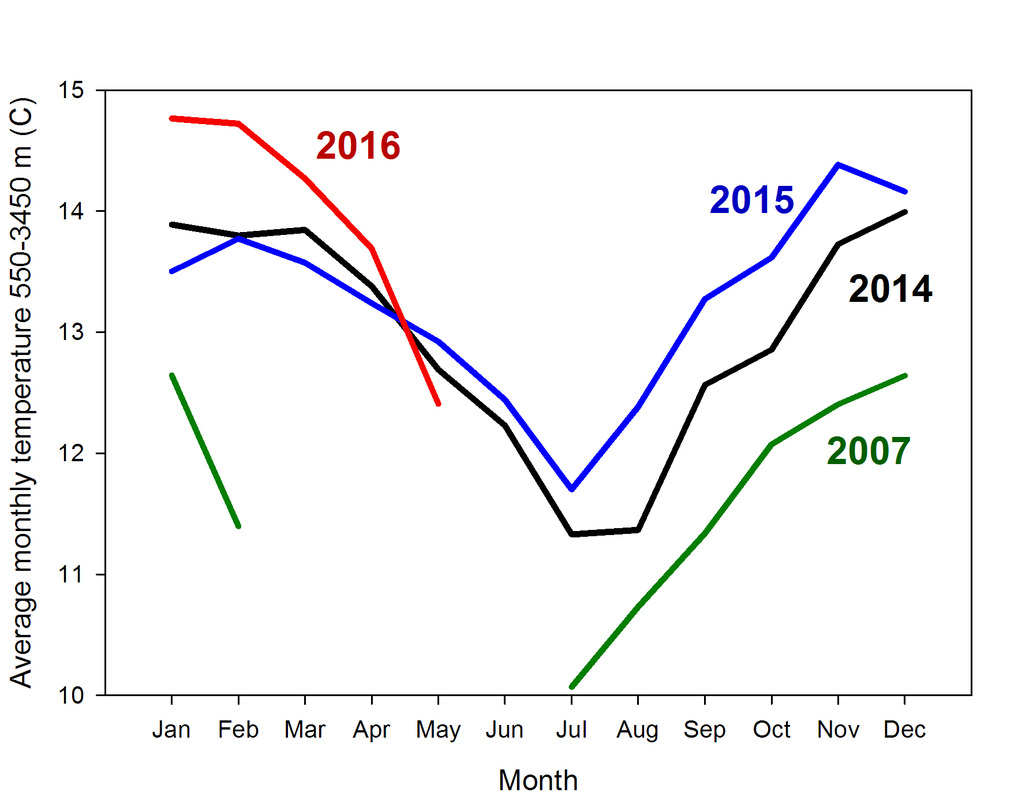

Back in March I posted some preliminary analyses showing average monthly temperatures in the leaf litter (habitat and breeding grounds of terrestrial-breeding frogs) across a wide elevational gradient (from 550 to 3500 m) in the eastern slopes of the Andes near Manu National Park in Peru. The previous graph was only showing temperature until the end of January, but we have now collected data until May, i.e. until beyond the end of the wet season (austral summer). Unfortunately, February was again much warmer than the previous two years, an anomaly that has been observed for the entire South American continent - according to NOAA, February 2016 was the warmest February in South America since 1910. The new data at Manu also suggest a return to more "normal" conditions --that is, if we assume 2014 and 2015, globally among the warmest on record, to be normal for this region. But how did 2014 and 2015 differ from previous years? We analyzed data collected in 2007 with similar iButtons (although with a cheaper model, with 1C accuracy as opposed to the version with 0.5C degrees accuracy that we use now) and at some of the same locations, but only within dense cloud forest from 1400 to 3500 m. We reduced the 2014-2016 dataset to mirror the structure of this 2007 dataset, and again compared the average temperatures across all elevations. The difference in temperatures between 2007 to 2016 is remarkable and exceeds 2C degrees for most of the last 10 months - to appreciate how this degree of warming is substantial for the region, think about Janzen's hypothesis about mountain passes being higher for tropical organisms. On average temperature decreases ~0.6C every 100 m of elevation, thus 2C warming corresponds to an elevational difference of >300 m. Organisms would have needed to shift their ranges upslope by ~300 m over 10 years to track the temperature range to which they were used to. Not an easy task for tiny frogs that live in extremely small home ranges. As a reminder, these temperature data were collected in the leaf litter and under a layer of mosses or dead leaves in the montane cloud forest. These microhabitats, where frogs spend most of their day, are thus thermally buffered from high and low extreme temperatures recorded, for example, by thermometers measuring air temperature. Whereas such thermal buffering provide some degree of protection from extreme heat events, our data show that leaf litter frogs are unlikely to escape from the gradual increase in temperatures.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

CATENAZZI LABNews from the lab Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed