|

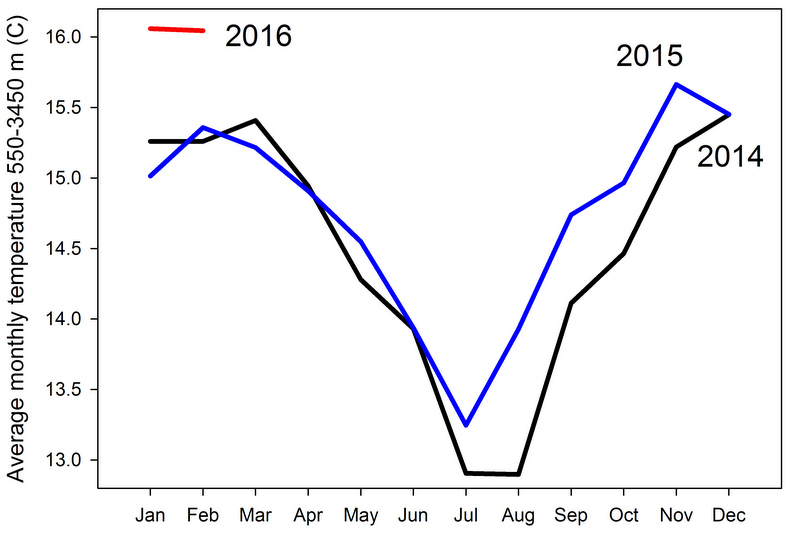

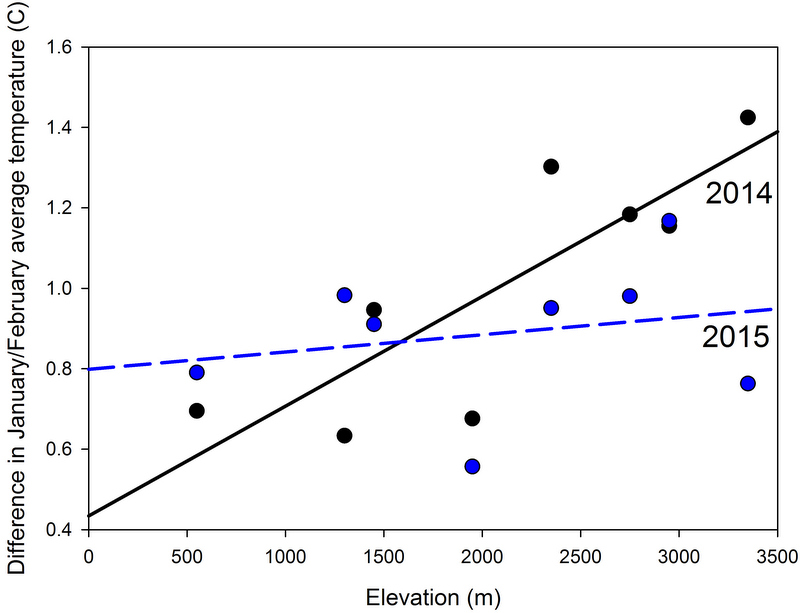

Last year was the warmest year on record but our data from Manu National Park in the eastern slopes of the Peruvian Andes show that January and February 2016 might shatter previous records in the region (January-March are typically the warmest months in this region). We only started tracking leaf litter temperatures (where our study critters the amphibians live) in January of 2014, and thus only have data since that time, but this is probably compensated by the fact that 2014 and 2015 are among the warmest years since records began. Our data for the first two months of 2016 along the elevational transect in Manu from 550 to 3450 m show that January and February 2016 are nearly a degree Celsius warmer than the same months in 2014, and ~0.8 Celsius warmer than the same months in 2015 (see graph below). What is remarkable in these data is that the sensors do not record air temperatures, but temperatures amphibians are likely to experience in their thermally buffered microhabitats, under layers of mosses (at high elevations) and leaf litter (at mid and low elevations). These data suggest that amphibians are unlikely to easily escape warming, even under layers of mosses and leaf litter. The photo shows sensors embedded in agar models being buried under the leaf litter in the montane forest at 900 m, which is the wettest among our monitoring sites. The sensors placed under the deepest layers of mosses (and thus, possibly more buffered against changes in air temperatures) recorded larger increases in warming than sensors placed under the thinner leaf litter. This is possibly caused by higher degree of warming at high elevations, as shown by the graph below which illustrates that average temperatures in the high-elevation cloud forests (above 2000 m) this year exceed by up to 1.4C the January-February averages of 2014.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

CATENAZZI LABNews from the lab Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed